Introduction

I have always had a fascination with all aspects of space travel. When I saw Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey,” back in 1969 I was enthralled with the idea of creating artificial gravity. I always wondered what that would be like and would it be exactly like it was portrayed in the movie. Recently I wrote a novel and wanted to incorporate spinning spaceships to simulate gravity during a long journey. I started to research the effects, especially the Coriolis Effect. I soon realized that it was not an easy research project. I found very little on the internet. Most sites on the Coriolis Effect were more interested in Earth’s weather patterns or how thrown balls on merry-go-rounds curve. I decided to do my own research and experiments to see for myself. I had to learn some new math for me. Vectors. What I needed were equations. This is the result. I have had a few people check and verify my math, and I encourage others to do the same. My conclusions are not to be accepted as proven fact. My conclusions are my own but do fit nicely with my experiments. There is a variance that will be addressed (see ** below) Basic algebra and trigonometry are helpful but not required to follow my reasoning. My final conclusions are that using centrifugal force to simulate gravity is not perfect and can be a bit dangerous under certain circumstances. My other article on this covers those aspects. Here you will find the methods to calculate the motions involved.

In a rotating spaceship, one may want to throw something, jump or run. Centrifugal forces and the Coriolis Effect act on motions in a rotating field. In this paper, we will be assuming a large spaceship in the form of a rotating ring for our examples. In a throw, jump or stride, as you leave the floor or a projectile leaves your hand, these forces affect the direction and velocity. I have determined that when the projectile does leave your hand, all the forces, accelerations, etc. end at the exact time that it leaves your hand. The same would apply to the last foot to leave the ground in a run or jump. The Coriolis Effect will no longer apply to any thing or person that is not in contact with the ship. Newton’s First Law of motion applies. A body at rest or moving at a constant speed in a straight line, will remain at rest or keep moving in a straight line at constant speed unless it is acted upon by a force.

*A quick note about units of measure. I will mostly be using meters but in a few places I will use feet for those Americans (like me) who still mostly think in feet. Since we are more interested in the final angle, the units of measure do not matter.

Calculating Final Vector

To calculate the direction and final velocity or vector of the new motion, the calculating method presented here would apply. When the rotational velocity is much greater than the throw, run, etc., the differences can be dramatic. If the velocity of this new motion is greater than the rotational velocity, the same calculations apply but the difference in the change of direction is considerably less. When the new motion’s velocity is greater than a factor of ten or more, the angle does not vary much from the intended target. It is when they are close to the same velocity that all the forces have the most effect on the motions.

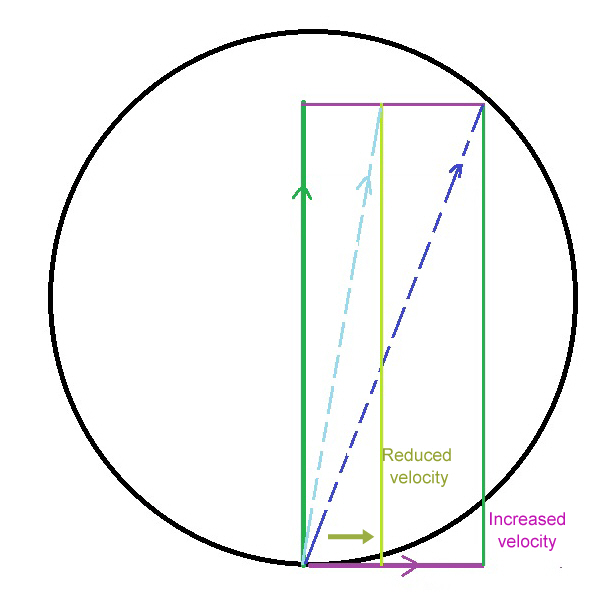

There is also a change in velocity from the rotational energy being added to or subtracted from the new motion. The velocity is added if in the direction of the rotation, and reduces until the angle of the new vector is at a 90 degree angle to the rotation, where it has no added velocity from the rotation. When the angle is greater than 90 degrees, the velocity of the new motion is reduced by the rotation until the rotational velocity is completely subtracted from the new velocity.

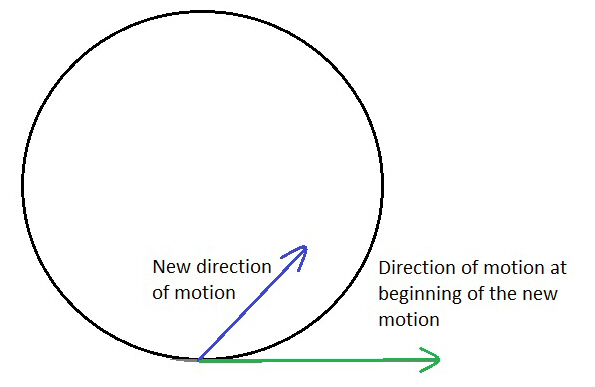

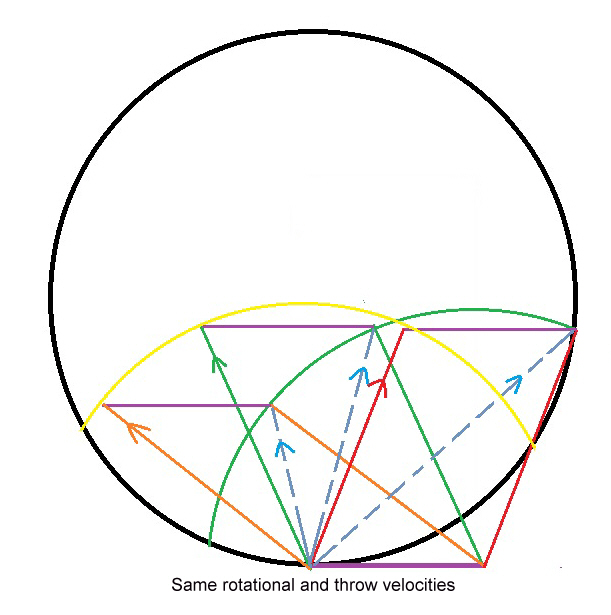

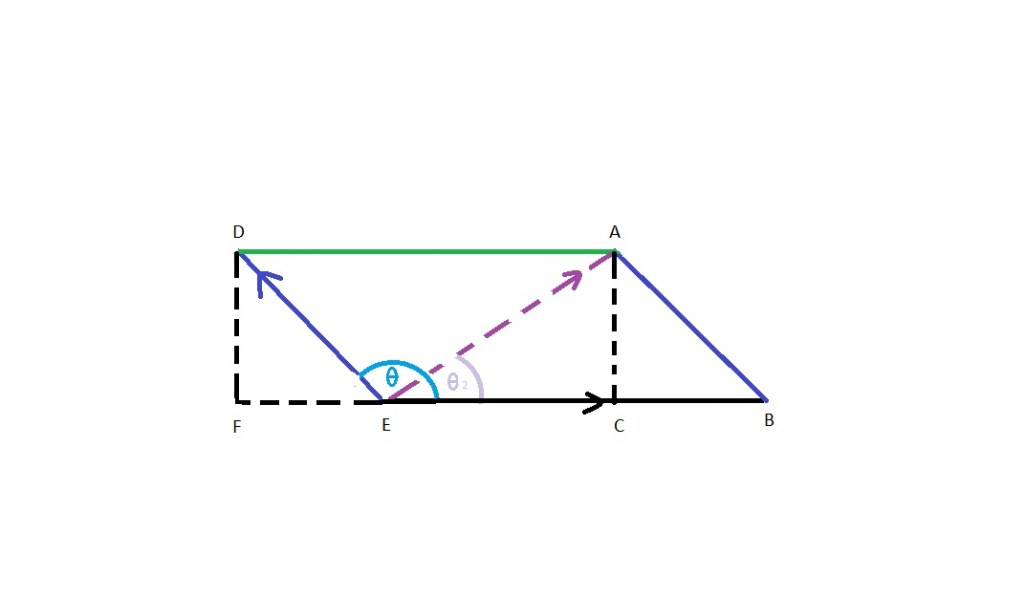

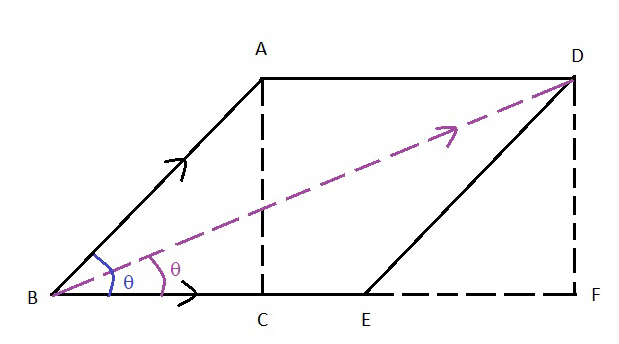

To calculate the new vector velocity, we need to know the original direction of the rotation. In this graphic we have the circular motion represented by a circle. The rotation direction and magnitude are represented here by the green arrow and the new motion is designated by the blue arrow. The new direction and motion can be in any direction inside the circle. The angle from the green line is theta (q). We will demonstrate calculating gravity gradients and rotational velocities later in the section for running.

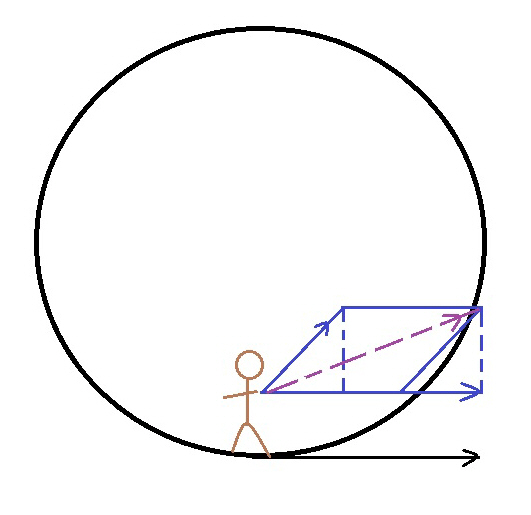

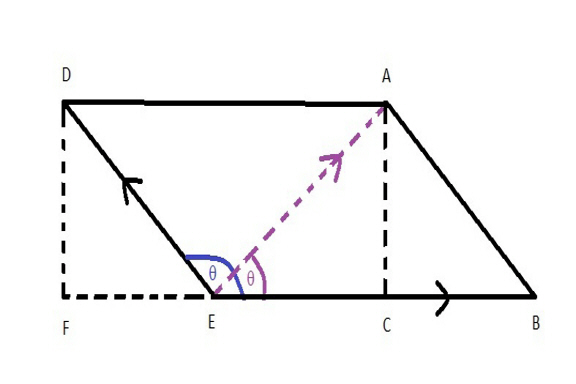

To calculate what the new direction and velocity will be three values need to be known. The rate of rotation, the new velocity from the change in direction and the angle of the new direction in relation to the direction at the time of the change. The following diagram will be the basis for our equations. Our goal is to predict the purple dotted line and its value. Each line is a representation of a velocity. For example, in our first diagram the green arrow might be in feet or meters per second. To designate the value of each arrow, we will assume that it is a period of one second. If the velocity of rotation is 15 feet per second (ft/sec), in one second it will have rotated 15 feet. The green line would be 15 feet long. If the blue line was 9 ft/ sec, then it will be 9 feet long. We are interested in the velocity of motion only at the moment the motions diverge. An important note is that at the time of a change in direction, the velocity from the rotation is exactly in the direction of the rotation. An example would be to drop a ball while rotating on a merry-go-round. The ball will travel at the velocity of the rotation and leave the carousel at a 90 degree angle to the hub at the time of the release. The action is the same as that used in a sling. The merry-go-round does add velocity to the ball.

This diagram shows the motions we will be predicting. It will be assumed that after our subject throws something, they will continue rotating at the velocity of the rotation and at the end of the throw, they will be at a different location in our diagram. This will be assumed and will be shown in a few diagrams. The apparent motion to a static individual in the ship will note the Coriolis Effect on the projectile but in our diagrams, it will look like it went straight from our point of view outside the rotating ship. In reality, it is traveling in a straight line to the outside world but curving due to the Coriolis Effect to any witnesses inside the ship.

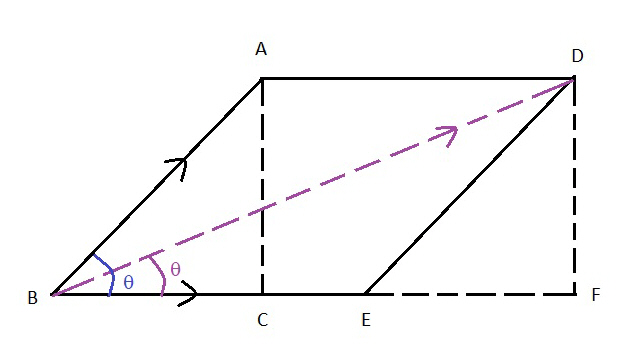

We will apply our equations to the diagram above. Line BE is the velocity of the rotation. Line BA is the new motion which could be a throw, a jump or a stride. The blue theta is the angle away from the rotation at the instant of the change in direction (usually designated as D). The purple theta will be the new angle after the forces average out.

Example

A smaller spaceship with a diameter of 15 meters is rotating to produce 1/6 G or one lunar gravity equivalent. It is rotating at 3.5 meters per second, taking 13.464 seconds to rotate to achieve this gravity gradient. An astronaut on board wants to toss a sandwich to a fellow astronaut a few meters in advance of the rotation. One meter above the floor, the astronaut tosses the sandwich at an angle form the floor of 35 degrees a meter above the floor which would normally be in a direct line to the other astronaut’s hands. The velocity of the toss is 2.9 meters per second. Where does the sandwich go? At one meter above the floor, the rate of rotation is 3.03 meters per second. To calculate this, first we have to find line DF above, then we can calculate BD, which will be our final angle and velocity.

Line BE is our rate of rotation or 3.03 MPS. Line BA is our toss of 2.9 MPS and q is 35 degrees. Line BA and line ED are equivalent so line ED is 2.9 MPS (actually the meters per second will all be one second in length, leaving us with just a distance in meters). We first calculate line DF. We use this equation to calculate DF.

sin 35 (ED) = DF

The sine of the angle of 35° = .573576. The length of ED = 2.9 (2.9 MPS x 1 second = 2.9 meters). .573576 x 2.9 = 1.66337. Line DF is 1.66337 meters (MPS). The sine of the angle (q) multiplied by the line DF gives us the “height” of our triangle. Next we calculate the length of EF.

cos 35 (ED) = EF

The cosine of the angle of 35° = .819152. ED = 2.9. .819152 x 2.9 = 2.37554. The length of EF = 2.37554 meters (MPS).

Next we add lines BE and EF to get the line BF. 3.03 + 2.37554 = 5.40554. Line BF = 5.40554 meters. To calculate line BD we can use the Pythagorean Theorem. BF2 + DF2 = BD2.

5.405542 = 29.2198629. 1.663372 = 2.766799757. 29.2198629 + 2.766799757 = 31.98666266.

√31.98666266 = 5.658675261. Line BD is about 5.66 meters long or the velocity of the toss is about 5.66 MPS. Next we need to calculate the angle of the toss.

Line DF / line BD = tangent .293850425. On a calculator (at least mine), enter tan-1, .293850425 = 16.38072164 degrees.

The sandwich would travel at an angle of 16.38 degrees at 5.66 MPS. The velocity of the rotation and the velocity of the toss would equal a velocity in relation to the outside world of 5.66 MPS.

This is what it might look like.

The dotted line figure represents both where the catching astronaut was at time of the throw and the throwing astronaut after one second. Our astronaut would miss her target, the sandwich landing near the feet of the other astronaut. Here’s hoping for a bounce.

Against the Rotation

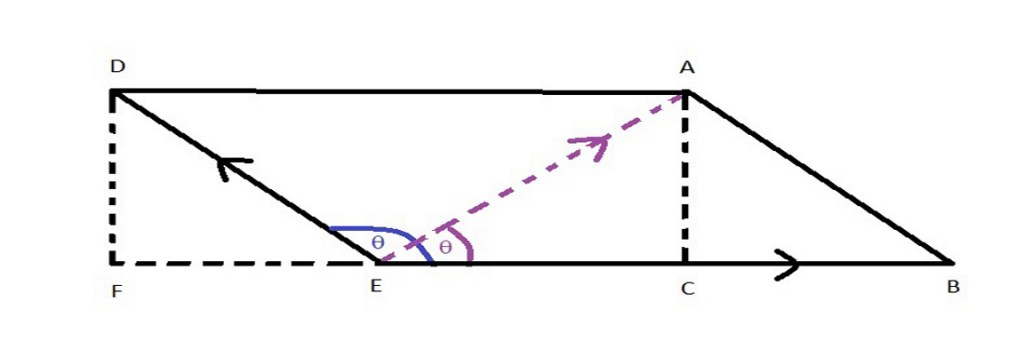

Now let us see where a throw against the rotation would go. This is a diagram of a throw in the opposite direction.

In this one, line EB is the velocity of the rotation, line ED is the velocity and direction of the throw. Line EA is our final velocity and direction. You may notice that if the throw approaches the velocity of the rotation, line EA will move more to the left as line ED lengthens as does line EA. The lower the velocity the throw moves more to the right. If the angle moves more to the left (or angle from rotation increases), the final angle does move considerably. As the angle approaches straight up, the angle moves left. I altered the diagram to demonstrate this. We will leave vertical throws for later.

Again, we know the angle of the throw (blue q), the velocity of the throw (line ED) and the velocity of the rotation (line EB). Again our goal is to calculate line EA which is the hypotenuse of triangle EC, AC, EA. First we need to find the length of line FE (which is equivalent to line CB).

We need figures again. We will use the example above for our example here. This time our astronaut is throwing the sandwich the other direction at the same angle from the floor at point of throw or 35 degrees and at a velocity of 2.9 MPS. Her hand is rotating around at 3.03 MPS again.

To find the angle (q blue) we need to subtract 35 from 180, which results in 145 degrees but we will be using the 35 degrees to find line EF.

sin 35 (ED) = DF

and,

cos 35 (ED) = EF

Sin 35 = .573576, line ED = 2.9. .576576 x 2.9 = 1.66337. Line DF is 1.66337 meters again.

Cos 35 = .819152, line ED = 2.9. .819152 x 2.9 = 2.37554. Line FE is 2.37554 meters long. It is the same as the first example but from here on it will diverge. This time we subtract line FE from line EB to get the length of line EC. Line EB = 3.03, therefore 3.03 – 2.37554 = .65446. Line EC = .65446. We can use the Pythagorean Theorem. EC2 + AC2 = EA2. .654462 = .42832. Since AC = DF, then 1.663372 = 2.7668. .42832 + 2.7668 = 3.19512. √3.19512 = 1.78749. Line EA = 1.78749 meters or MPS over one second again. Next we need to calculate the final angle of the throw. AC/EC = tangent 2.54159. Again using a calculator, tan-1, 2.54159 = 68.5226 degrees.

The sandwich would travel 1.78749 meters in one second at an angle of 68.5226 degrees to the rotation. Here is another graphic representation of what that would look like.

Again the figures switch places as the ship rotates in one second. The straight light purple line is the direction of the throw. The brown arrow shows path of the sandwich to the outside world. The light purple arrow is the path the sandwich takes to the astronauts showing the Coriolis Effect in action. The dotted astronaut is the new location of the thrower after one second. The sandwich sales over the second astronauts head but at a lower velocity than originally thrown.

In a vertical throw, the rotational velocity affects the direction but as the velocity of the throw increases, the transfer of velocity from the rotation is greatly reduced as seen in this diagram. It is here that I found a variation in my experiments (launching projectiles from a 1960’s toy tank, see images below). One of my test projectiles launched too early but then landed where I predicted it would. This means the velocity that was subtracted by the rotation was a little less than calculated. I was not able to launch my projectiles exactly when I wanted and I was not always successful in calculating the exact velocities involved. In launches in the direction of the rotation, my predictions were quite accurate. My best guess is that the amount of change to the velocity of the throw, or launch in this case, is of a greater degree and any miscalculation or variance in the launch velocity, is aggravated. ** I also had to deal with wind and the aerodynamics of the projectiles which may have affected the results.

I would like to perform these tests under more controlled conditions on a large carousel or merry-go-round, using heavier balls (such as baseballs) that are less affected by wind resistance. The problem here is that the playground carousels have been outlawed in my state. If anyone would like to perform these experiments I would be interested in the results.

** After considerable analyzing of the original video, I have found that the velocities were different than I had predicted and measured at the time. The carousel slowed more than I had originally calculated and the little tank had launched the missile at a slightly higher velocity. Doing the original calculations again, if we start with the angle of launch at 38 degrees (which is less than the 45 I had used in my original calculation which is the largest discrepancy) and more accurate estimated velocities of 8.6 ft/sec for the rotation and 10.3 ft/sec for the missile’s final velocity. Recalculating I get an original missile velocity of 15.67 ft/sec (very close to my original tests of the tank). This results in a final velocity of about 10.3 ft/sec and a final angle of 70 degrees, not the 110 I originally predicted. Very close to what we see in the video. The rotation was slowing rapidly and my string slowed it even more when it triggered the launch. A fun side investigation but we (I) digress…

Various Throws

In a vertical throw, the rotational velocity affects the direction but as the velocity of the throw increases, the transfer of velocity from the rotation is greatly reduced as seen in this diagram.

Various angles away from the rotation at the same velocities have lessening added velocity from the throw until the throw is just past the vertical where the velocity of the throw’s vector equals the exact opposite angle of the throw from 90 degrees as seen in this diagram. Such as a throw at 110 degrees away from the rotation would have a vector angle of 70 degrees. At this point the initial velocity of the throw is equal to the final velocity. After that point is passed, the vector velocity has a lower velocity than the original throw. The following diagram demonstrates this.

The yellow arc demonstrates the throws all have the same velocity. The green arc shows that there is a relationship of the vector to the velocity of the rotation. There must be a mathematical principle explaining this but I will leave that for another time.

Running

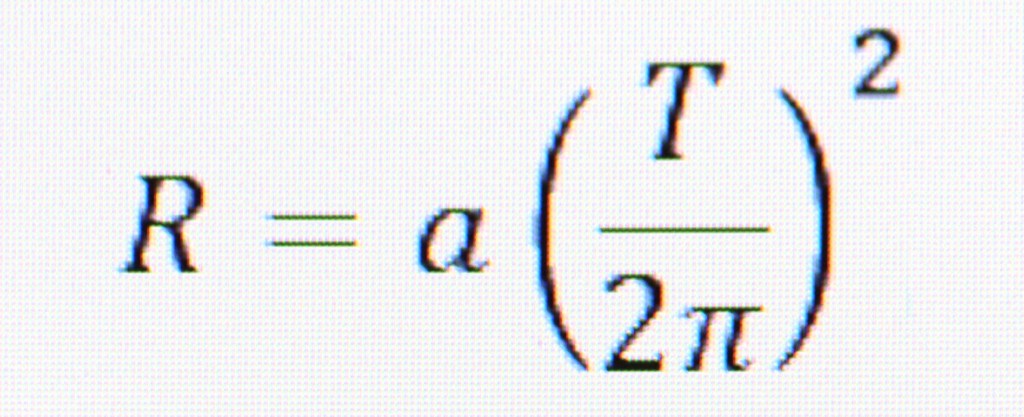

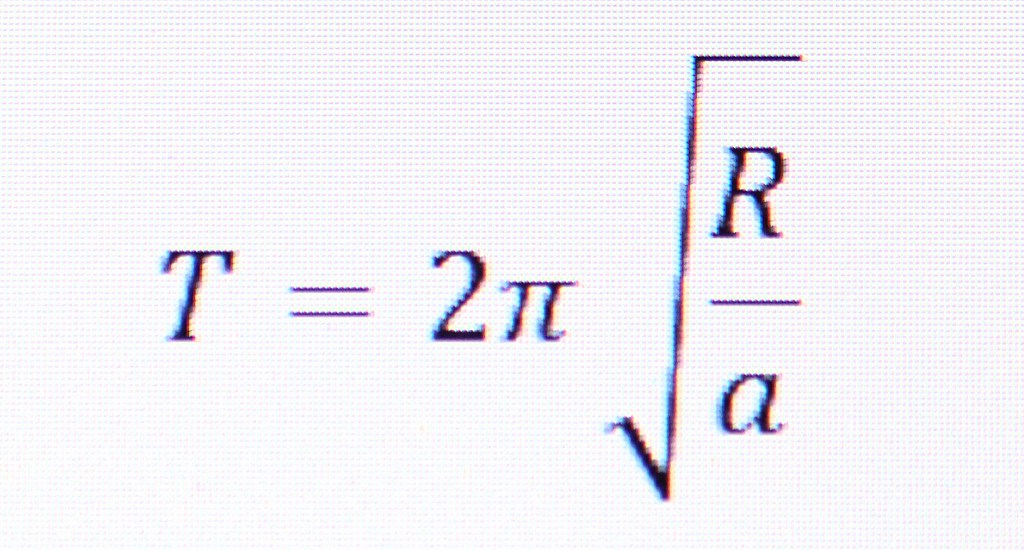

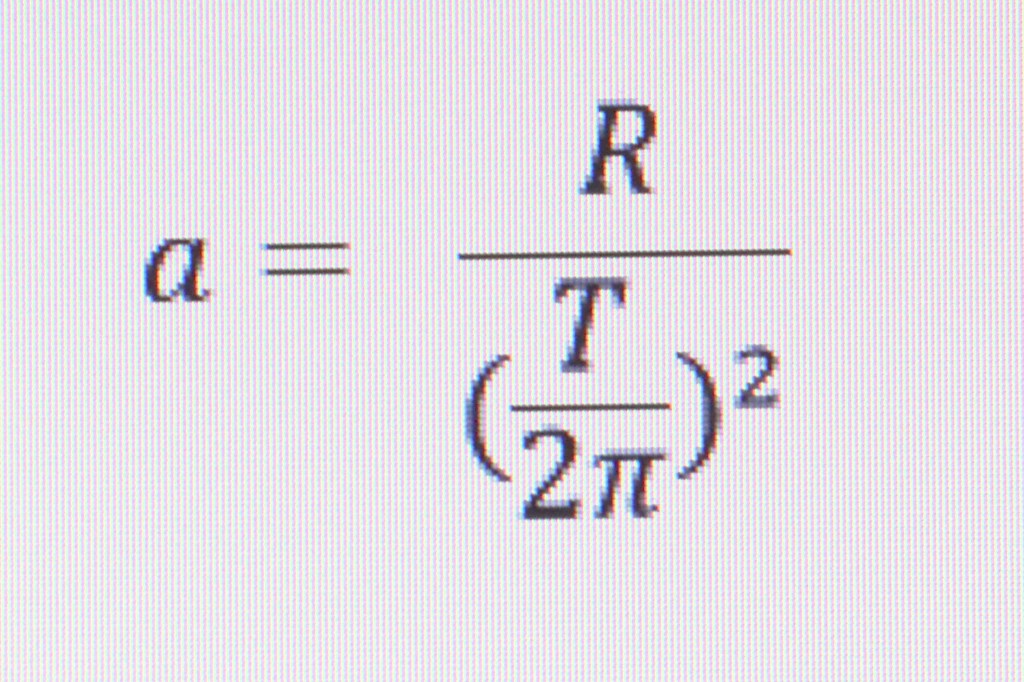

Walking would be relatively easy unless the gravity gradient was very low. We can demonstrate this by increasing the angles and velocities in a run’s stride. This will demonstrate the differences in the directions and angles that are exaggerated in a run. A great example of running in a rotating ship was shown in the motion picture “2001: A Space Odyssey.” Actor Gary Lockwood was seen jogging around a rotating ring inside their interplanetary space ship. The author Arthur C. Clark wrote the book and co-wrote the screenplay with Stanley Kubrick the producer and director. They described the ring as being a centrifuge that was 35 feet in diameter. It was rotating at one revolution in ten seconds. Using an equation we can calculate velocity of rotation and the gravity gradient (we will calculate in feet this time). To calculate the radius of a spinning ring to get a desired acceleration, the equation is: a = v2/R, where “a”, is the acceleration, “v”, is the velocity of the rotation and “R”, is the radius of the rotating ship. More equations are shown below. These are useful when the velocity is unknown or you want to solve for Radius, Time or Acceleration.

Again, “R” is the radius, “a” is the acceleration and “T” is the time in seconds of one complete rotation. If you know the radius and the acceleration you need, to find the time necessary to spin the ship to achieve that acceleration, the equation is:

Next, if you know the radius and the time, you can calculate the acceleration:

When we plug in our know values we get an acceleration of 6.908723081 ft/sec2. One fifth Earth gravity (G) is 6.4 so a spinning spaceship would experience about one fifth “G” at this size and rate of spin.

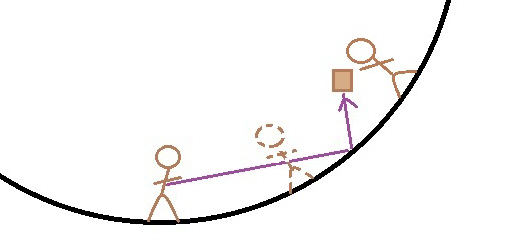

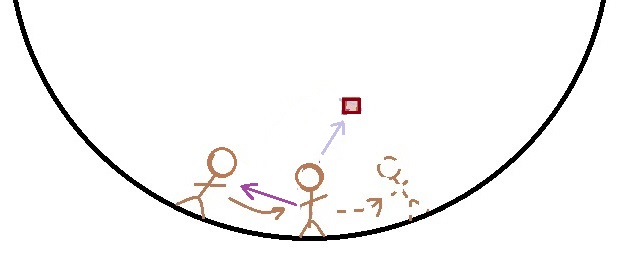

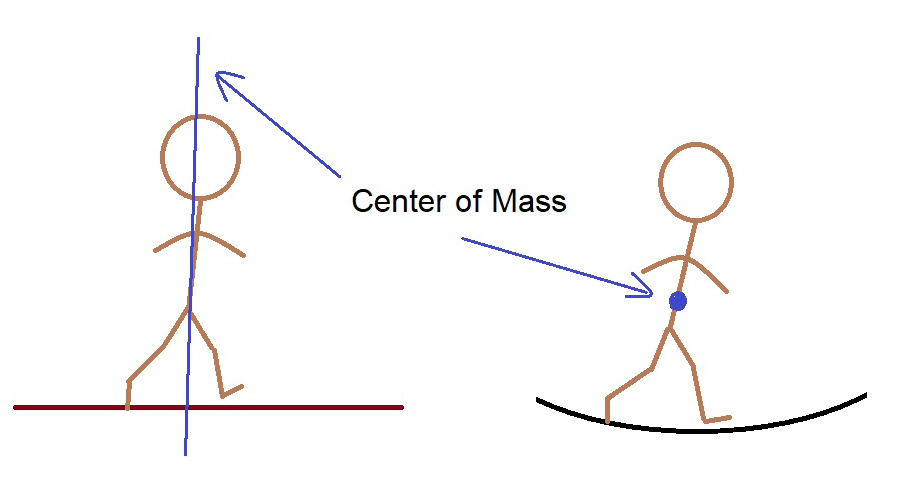

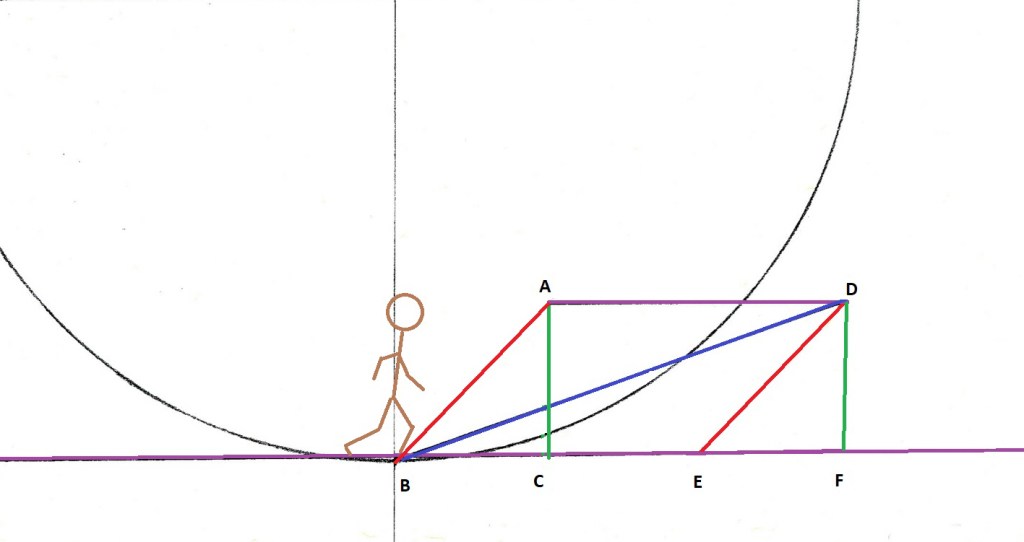

In the movie, character Frank Poole was jogging around the circumference of the centrifuge. I estimated his jog at a speed of 4.6 MPH which is about 3.13636 ft/sec. The centrifuge is spinning at 10.995574 ft/sec. We will round off to 3.15 and 11 for now. A jog in the direction of spin will be calculated first. This has a large difference between spin and jog. The angle of the slope will be arbitrary. The curve of the floor during one stride is close to about 5 degrees. I’ll save you the time. With these figures, the angle of slope is less than one degree and the difference in distance was less than 1/1000. It would seem perfectly normal. The movie was quite accurate. The only real difference is his center of mass. On Earth your center of mass is on a line drawn through your body and aimed at the center of Earth. In space, only your movements dictate the forces and thus your center of mass is near your waist. Any force on your feet and your body starts rotating around that center (when stationary or moving slowly, the center of mass is in a line with the hub). Here is a graphic representation of that phenomenon.

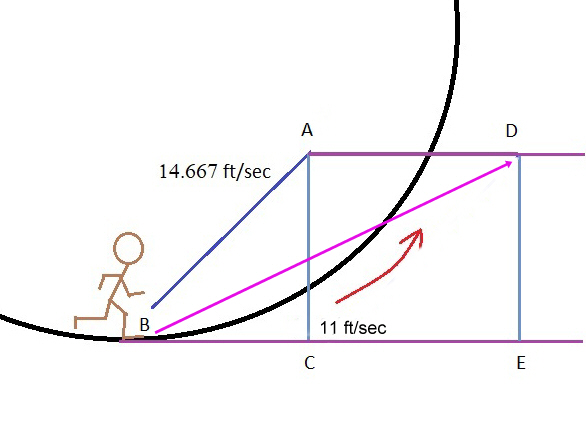

I also calculated a run of 10 MPH which is 14.66667 ft/sec. A person running in a centrifuge could change their angle quite easily to adapt to the curvature. I will calculate an angle that slightly anticipates where a stride would take them with a curvature of a ship this size. 10 degrees is a good guess. I call the angle an astronaut would aim their stride up to account for the curvature the “stride slope.” In this case our final location of our runner after one second puts her outside the centrifuge. Our astronaut would stumble. We will have to rethink this. Anticipating the distance we estimated after one second would put our astronaut nearly one quarter of the way around the centrifuge. This time I will do the calculations for a run of 10 MPH and a “stride slope” aimed up about 45 degrees.

This is a graphic representation of our calculation with these figures. I will not show all the steps since we covered that in a throw above.

This is much better as her stride is closer to the floor. “D” is outside the circle after one second but this will make it feel like running uphill. All our astronaut would have to do is adjust the body angle to compensate for her center of mass and the curvature.

In reality, it would take practice to see what the stride slope should be with a normal running stride length and frequency. It should work nicely. An astronaut may take two or more strides per second and if they angle their body to balance the angles in relation to their center of mass, they could be ready for the next stride and not land on their face. As you can see, a jump would be a problem.

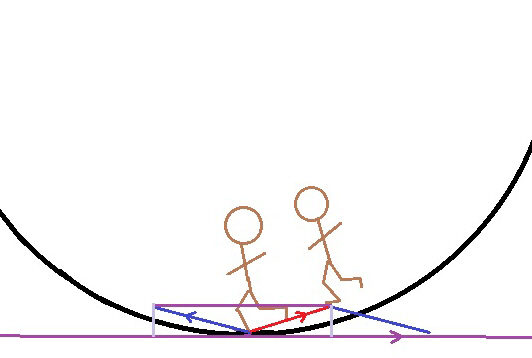

How about a run in the opposite direction?

We will calculate a 4.6 MPH jog to match 2001: A Space Odyssey. Our diagram again is:

This time we will anticipate a drift up from the floor. We will select 15° as our stride slope angle. We will also choose one stride as our speed and distance unit. At 4.6 MPH, I calculated two and a half strides per second. That is .4 seconds per stride. All of our velocities will be 40% of the previous velocities. Our 4.6 MPH or 6.75 ft/sec is now 2.7 ft/unit time. Rotational velocity is now 4.4.

Sin (q) x ED = DF. Cos (q) x Ed = FE. q = 15, sin q = .258819. Cos q = .965925826. DE = 2.7.

Then,

Sin (15) = .258819. .258819 x 2.7 = .6988.

Cos (15) = .965925826. .965925826 x 2.7 = 2.608.

AC = DF. DF = .6988. FE = 2.608.

EB – FE = EC. 4.4 – 2.608 = 1.792. EC = 1.792.

EC2 + AC2 = EA2. 1.7922 (3.211264) + .69882 (.48832144) = 3.69958544. √3.69958544 = 1.92343. EA = 1.92343. AC/EC = tan (theta new or theta2). .6988/1.792 = .389955357. Tan (.389955357) = 21.3°.

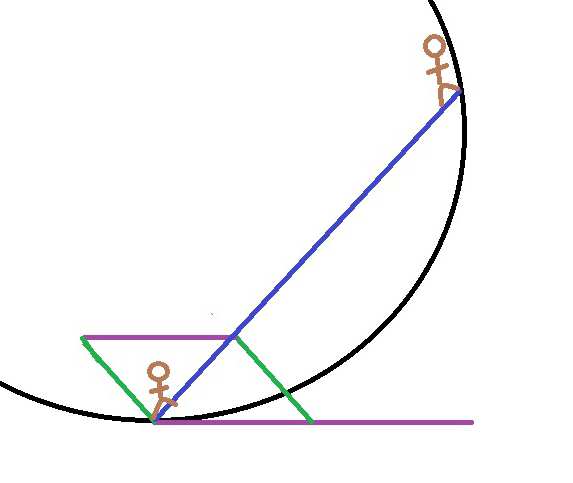

To recap, one stride at a 4.6 MPH jog, with a 15° stride slope will result in a new angle of 21.3°. There is a backwards drift of 1.92343 feet. The ship has rotated 4.4 feet along its circumference which translates to 14.4°. 1.92343 feet from the rotation of 4.4 = about 2.5 feet, close to the stride length. The curvature would reduce that. Our astronaut would be the correct distance traveled for one stride. Unfortunately, our astronaut would be about a half of a foot above the floor and not able to take another stride. What this demonstrates is that a jog against the rotation would work with a proper stride. But too much of a push off will propel you away from the floor and you will not contact the floor for another stride. You may also land on your back. The stride slope will be very shallow. Here is a graphic representation of this scenario.

Jumping

We have seen that it is the angle that you leave the floor that is the most important factor. As the radius and rotation increase, things get easier. In a small ship, with a low gravity gradient, it becomes more problematic and perhaps dangerous. There are several scenarios but we will concentrate on only four for two types of spacecraft. One large, one small. The jumps will have two each with and two against the rotation. The two jumps will be straight up and at a 45 degree angle. I will only show the solutions for a small ship against the rotation and a large ship with the rotation. The results of the others will only have the final results displayed. Again our small ship will be the 35 foot diameter centrifuge rotating at 10 seconds per revolution and the large ship will be a 100 meter ship rotation once every 30 seconds. Using both English and metric units will demonstrate the flexibility of the method.

With jump one our ship is 35 feet in diameter and is rotating at 11 ft/sec. The gravity gradient is about 1/5 G or 6.9087 ft/sec2. Our astronaut is going to jump with the rotation at 8 ft/sec (on Earth she would reach a height of one foot in a vertical jump). The jump is aimed at a 45 degree angle to the floor as she jumps. Remember our diagram:

Line BE is our rotation velocity or 11 ft/sec. (35p/10). Line BA is our jump velocity of 8 ft/sec. q Initial is our jump angle of 45°.

Sin q x BA = AC and FD. Cos q x BA = BC and EF. BE + EF = BF. BF2 + DF2 = BD2. √BD2 = BD. DF/BD = tan q final (final jump angle). Tan q final = jump velocity.

Sin (45) = .707106781. .707106781 x 8 = 5.656854249. It should be remembered that a right triangle with an angle of 45° has equal base and height (cos (45) x 8 = 5.656854249).

11(BE) + 5.656854249 (EF) = 16.656854249 (BF). 277.4507935 (BF2) + 32 (DF2) = 309.4507935 (FD2). √309.4507935 = 17.59 (BD). Velocity final of jump is 17.59 ft/sec. 5.656854249 (DF) / 16.656854249 (BD) = .339611199 (tan q final). Tan .339611199= 18.758° (q final).

Our astronaut will jump at an angle of 18.758 degrees at 17.59 ft/sec.

This is a graphic representation of the jump. In essence it would only be a hop that would land after traveling about 11 feet after about six tenths of a second.

A jump against the rotation will result in a jump at 7.781337065 ft/sec at 46.63357294 degrees. She will travel about 25 feet before landing on the floor, while the ship will have rotated 35.729 ft. It will take about 3.25 seconds and she will land on her back! Here is a simplified graphic of the jump. Her jump is to the left, while to us she moved to the right, in the direction of the rotation. At least she will have moved about ten feet from the start of the jump.

Applying the same angle and magnitude of the jump to a larger, faster rotating ship would have a different outcome. Let’s apply them to a ship 100 meters in diameter at the floor and rotating once every 30 seconds. The velocity of the “floor” is 10.47 meters per second (MPS). Applying our equation for acceleration we see that it has a gravity gradient of 2.19 meters/sec2. This is equivalent to about 1/5 Earth gravity (imagine that. Actually I planned it that way). Our astronaut jumps at 2.384 MPS (8 ft/sec) at 45 degrees with the rotation. Her final angle would be 7.821434974 degrees. Barely above the curve of the floor. Her final velocity (to the outside world) would be 12.27207421 MPS. As close as I can figure the curve, she would land on the floor slightly over a second after her jump. She would have traveled relative to the floor about 1.8 to 2 meters. This seems very close to what the astronauts did on the moon when they “bunny hopped.” It would be easy to adjust your angle for the proper distance.

Now let’s figure a jump against the rotation. I’ll save you the math again. She will jump at an angle of 45 degrees again at 2.384 MPS (8 ft/sec). Her final angle would be 10.78802892 degrees. She would be traveling at 8.947014122 MPS in relation to the outside world. She would be 1.685742566 meters above the floor and be about 1.3 meters behind the rotation. It would take about 2 seconds to reach the floor, she would travel about 18 meters and land nearly three meters behind the rotation. As seen from the point she left the floor, it would look like she jumped about 2.6 meters. This also mimics a jump on the moon but it is the angle that makes it travel farther.

You can immediately see the difference in jumping with as opposed to against the rotation. Runs and jumps with the rotation would seem almost normal. Against the rotation would seem to be in slow motion and more difficult to judge the angle needed. Another way to look at it is a jump with the rotation hinders the angle of the jump and adds energy to it. Against the rotation magnifies the angle but hinders the energy of the jump. They do not balance out.

Now let’s consider jumps that are straight up. First is our 35 foot ship. Again, 8 ft/sec jump but at a 90 degree angle or straight for the hub. This time the only math necessary is our base (11 ft/sec), our jump (8 ft/sec) and our final angle and velocity. Our final angle is 30.46283776 degrees. Final velocity is 13.60147051 ft/sec. She will travel about 20.5 feet (as far as I can calculate) in slightly over 1.5 seconds. The ship will have rotated 16.579 feet. Since the floor is curving but the jump is not, the final length of the jump in relation to the floor is about 5 feet. Again, she will not rotate to the outside world but will in relation to the floor (Coriolis Effect in action) and land on her side.

In our 100 meter ship, our base is 10.47 meters, our vertical velocity is 2.384 MPS. Again, much simpler calculation since all we are figuring is the final angle and velocity like a square that has been bisected diagonally. Our final angle is 12.51752301 degrees at 10.73798659 MPS. She would be in the air for nearly two seconds, travel about 21.2 meters before meeting the floor. She would land a little over 1.1 meters from where she jumped. This time her rotation in the air in relation to the floor is much smaller.

Final conclusions: Even though the gravity gradient is nearly identical in both ships, the results of jumps varies significantly. The smaller ship has a substantial difference resulting from the direction of the jump. The larger ship varies only about 60 to 70% according to the direction, the smaller ship has a difference of about 180%. The vertical jumps vary in distance by only about a foot but the curvature of the ship makes a significant difference on the angle the astronaut rotates. An interesting side note is that a jump at a right angle to the rotation would look virtually the same as a vertical jump. The landing at an angle and the drift in the direction of the rotation would be the same but have a correspondingly increased lateral distance.

Conclusions

Using centrifugal force to simulate gravity is not just a simple way to copy gravity. It is possible as long as you remember that there are differences and the Coriolis Effect can cause some surprises. The larger the ship and the greater the gravity gradient, the closer it is to what we are used to on the surface of Earth. The smaller the ship and the lower the gravity gradient, the more the differences become apparent. The direction you move, walk run or jump makes a difference in the results. In a slower rotating ship, the greater the possibility any movement away from the direction of rotation may become uncontrollable and even dangerous.

The effects of long duration space travel can be minimized by rotating a ship to simulate gravity. Just be aware it is not a perfect environment. With a little practice, it will become easier. Perhaps even fun. Just don’t throw a sandwich to a fellow astronaut across the ship and expect them to catch it on the first try.

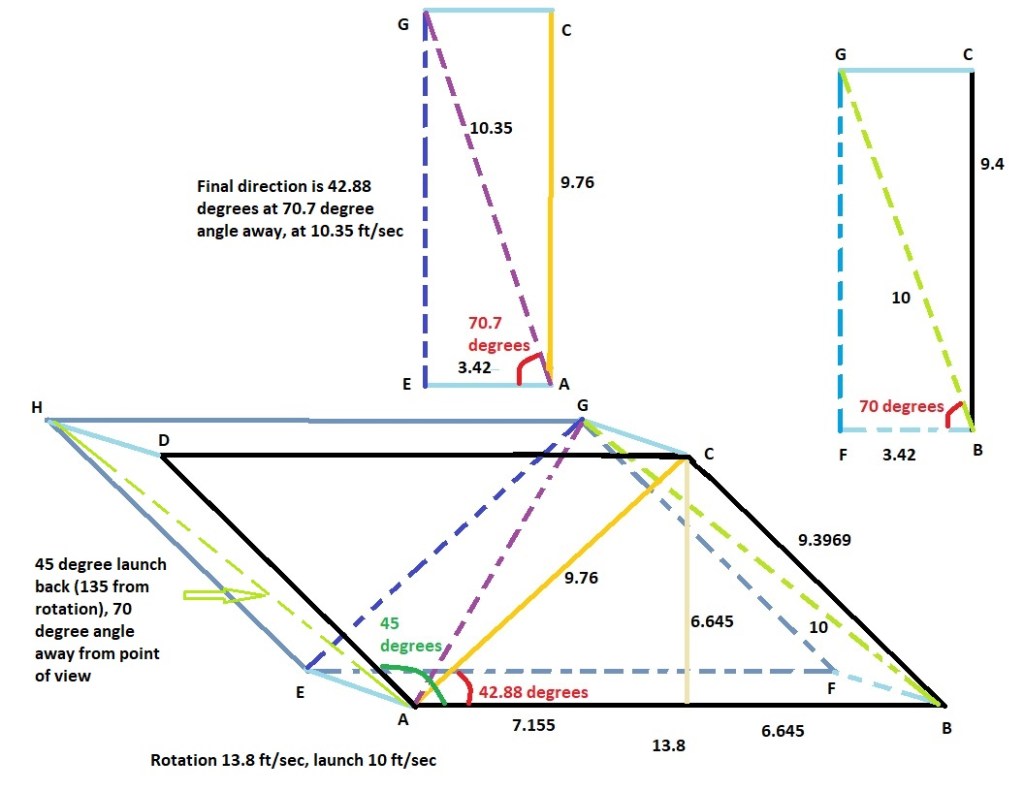

I tried my hand at three dimensional vectors and this is what I came up with. In order to know if I have it correct, I need to verify my math and try experiments. Feel free to critique my effort.

AB is rotational velocity. AH is the direction of the throw. AG is the final direction of the throw.

Rotation is 13.8 ft/sec. Angle is back 135 degrees from direction of rotation and at an angle away from the rotation of 70 degrees. Throw is 10 ft/sec. Final vector is 42.88 degrees back from direction of rotation at an angle from rotation of 70.7 degrees. Final velocity of throw is 10.35 ft/sec. How’d I do?